“Is the share market more volatile than it used to be?”

Whilst volatility technically refers to the frequency and magnitude of both positive and negative stock market price movements, this question only tends to get tossed around when there is a prolonged market downturn, as investors seeks reasons for (or perhaps, absolution from) their poor portfolio performance.

To answer this question, we need to clarify exactly what is being asked. Do we mean today’s market compared the long-term average? The change in volatility since the turn of the century? Are we talking about daily volatility? Yearly? On an individual stock basis or on a market index basis? I believe that by bettering our understanding of modern market volatility, we can better regulate our emotional responses, and ultimately improve our investing returns.

Let’s start by looking at some flat data and making some observations, and we’ll finish with some significant studies and potential explanations for what we are seeing.

Daily Percentage Price Fluctuations

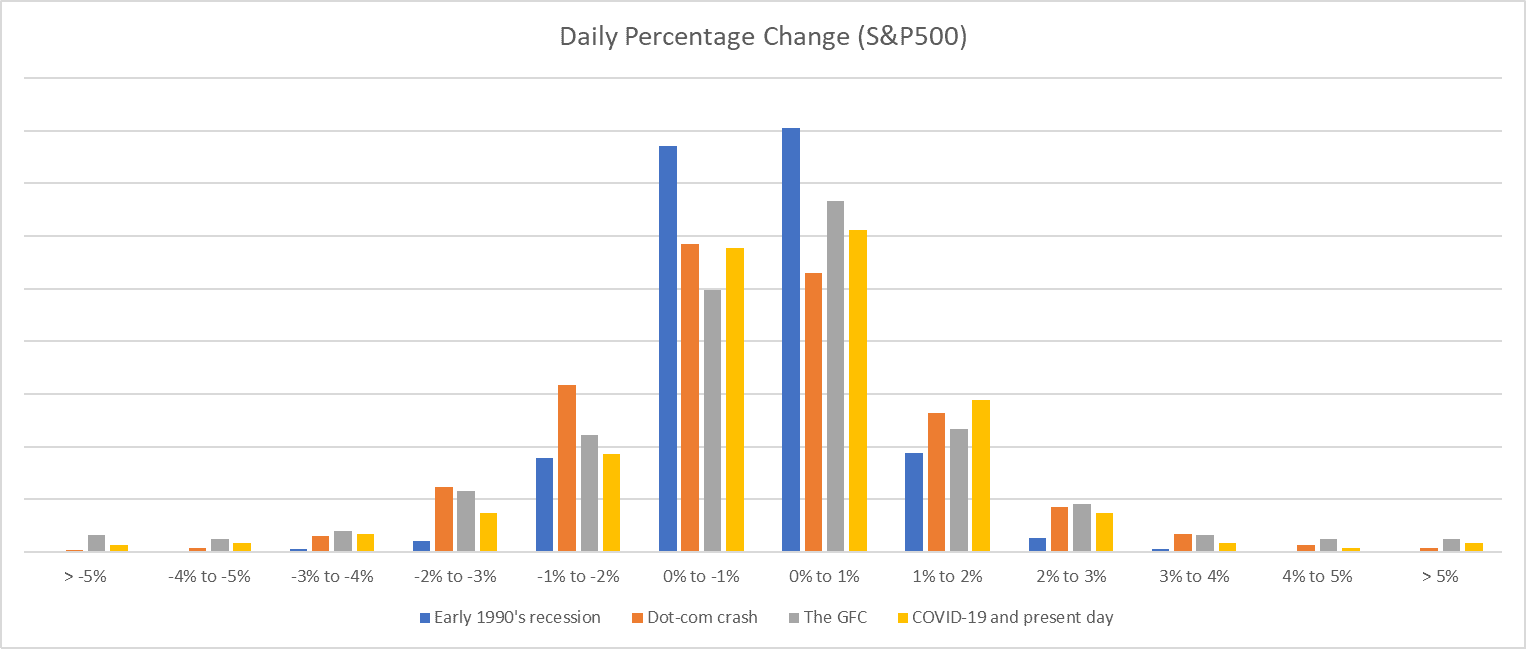

Looking at the S&P500, I started by plotting and comparing the daily percentage price fluctuations across four arbitrary dates ranges, which I felt roughly encompassed:

- The early 1990’s recession – 01/01/1990 to 01/01/1993

- The Dot-com crash and 9/11 – 01/01/2000 to 01/01/2003

- The Global Financial Crisis – 01/01/2007 to 01/01/2010

- COVID-19 and the present day – 01/01/2020 to 15/11/2022

The results can be modelled a few different ways:

| -1% to 1% | -2% to 2% | |

| Early 1990’s recession | 78.8% | 97.1% |

| Dot-com crash | 55.8% | 84.8% |

| The GFC | 58.2% | 81.0% |

| COVID-19 and present day | 59.4% | 83.1% |

| ≤ -2% | ≥ +2% | |

| Early 1990’s recession | 1.3% | 1.6% |

| Dot-com crash | 8.1% | 7.1% |

| The GFC | 10.6% | 8.5% |

| COVID-19 and present day | 6.9% | 5.7% |

| ≤ -3% | ≥ +3% | |

| Early 1990’s recession | 0.3% | 0.3% |

| Dot-com crash | 2.0% | 2.8% |

| The GFC | 4.8% | 4.0% |

| COVID-19 and present day | 3.2% | 2.0% |

So, what observations can we make?

Firstly, the 1990’s recession has more price stability than any other period examined. Whilst this is perhaps unsurprising when compared to the dot-com crash and the GFC, it is interesting when compared to the present day, since the U.S. has yet to experience a technical recession. A good argument could be made that the time surrounding recessions tends to be more volatile than the recession itself, however given that the early 1990’s recession only lasted 8 months, I think sufficient ‘normalcy’ is built into the two-year timeframe used.

The data also suggests that the GFC remains arguably the most volatile of the periods compared, with a consistently high number of days at high daily percentages changes.

Finally, similarities can be drawn between the dot-com crash and the present day, with the present day being slightly more stable overall, but having more instances of extreme (4-5%+) movements in either direction, particularly when negative.

Standard Deviation of Returns

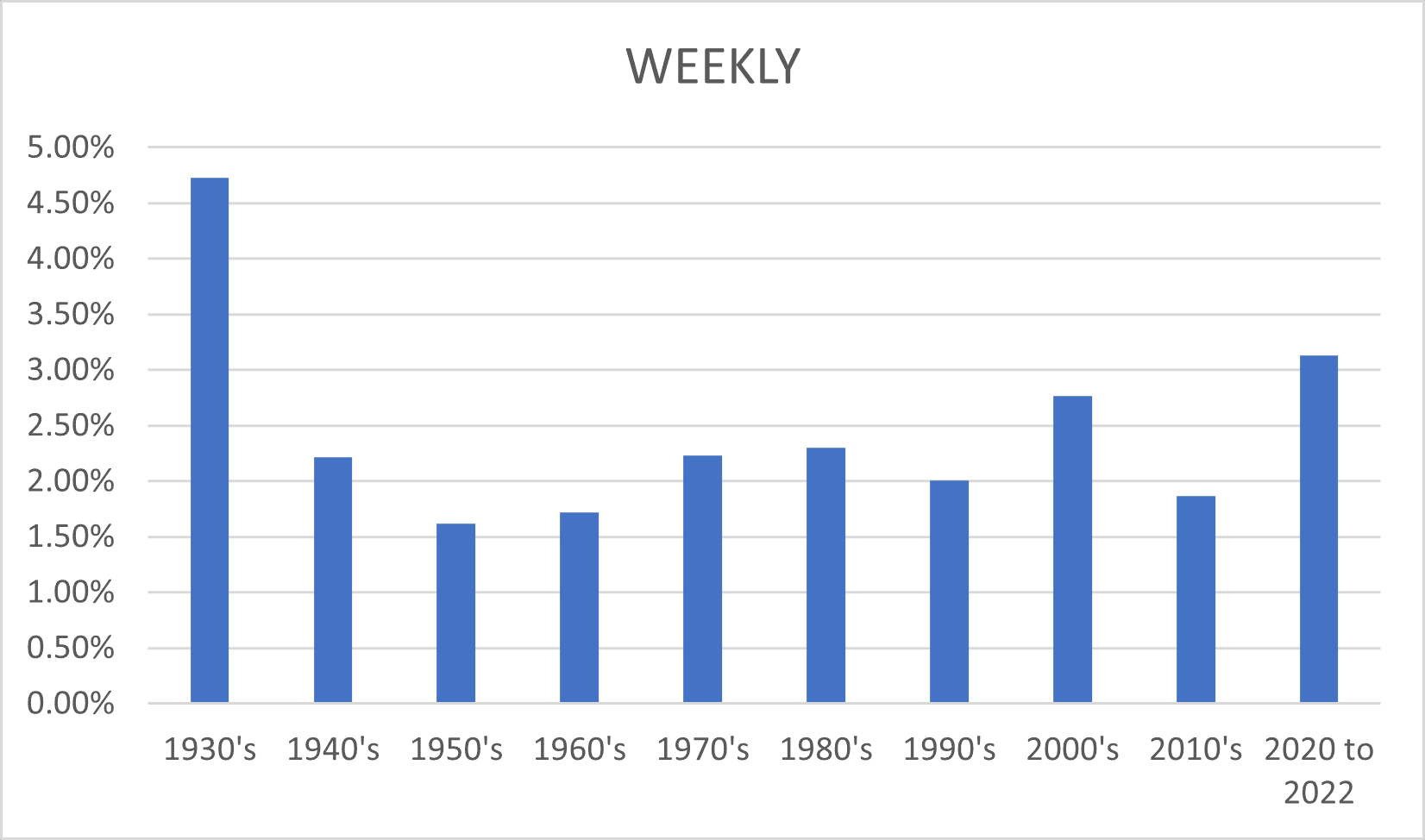

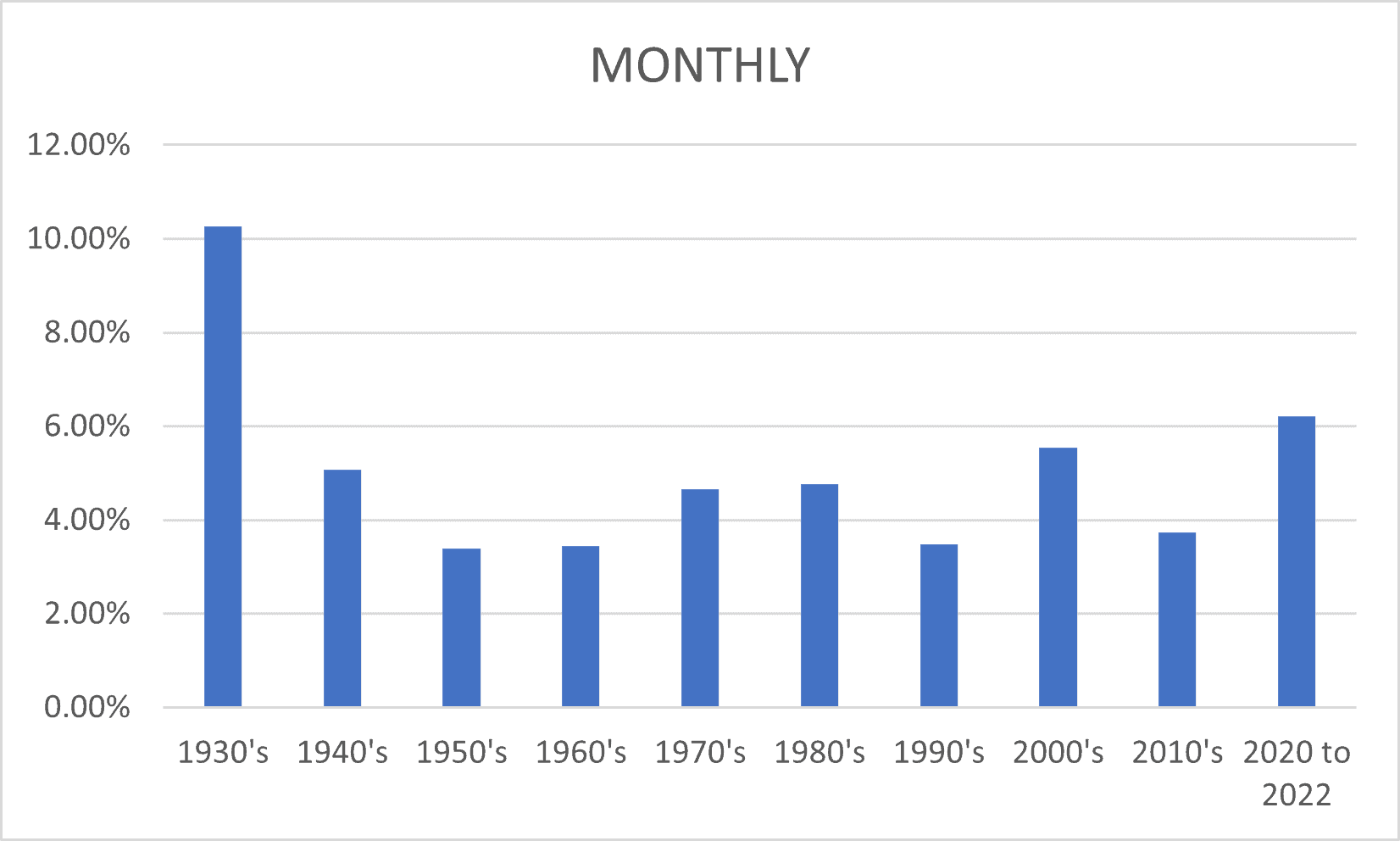

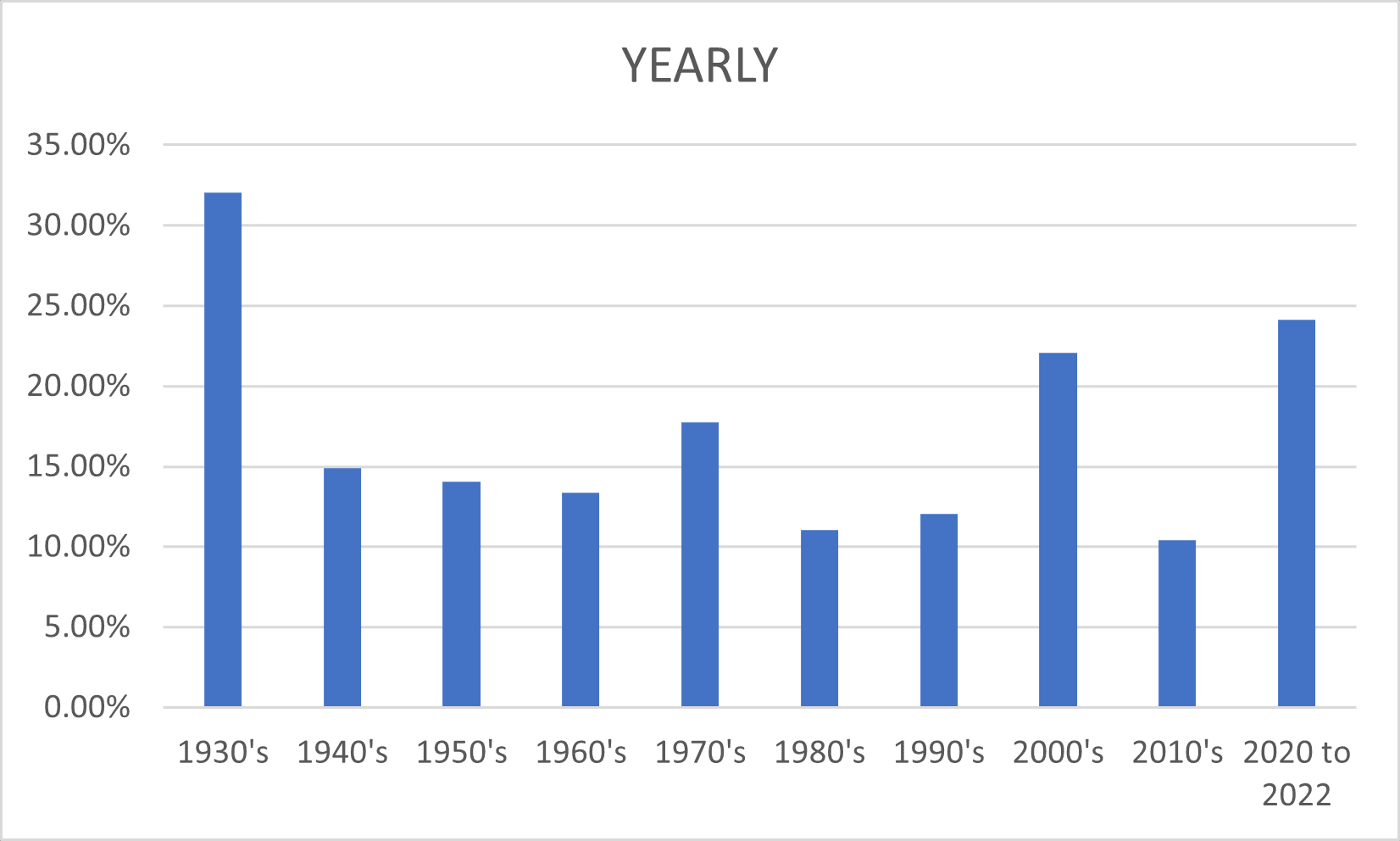

Now let’s measure volatility a different way, by looking at the standard deviation of returns for the S&P500 since the 1930’s, on a daily, weekly, monthly, and annual basis. This yields the following:

What does this tell us?

As an opening remark, we can see that regardless of the time frame used, the general shape of these graphs remains the same, making observations much easier to apply across the board.

In isolation, the last two years have undoubtedly been very volatile compared to previous periods, whilst obviously not benefitting from the smoothing of returns offered by the 10-year timeframes.

We can also see that the 2000’s were wild day-to-day, smoothed slightly over longer periods, but not by much. In comparison, the period immediately following World War II experienced the greatest level of stability of recorded history.

The 2010’s were the least volatile period that had been experienced for the previous 4 decades, which is something that rarely gets media attention. And finally, the great depression was far-and-away the most volatile period in recorded history.

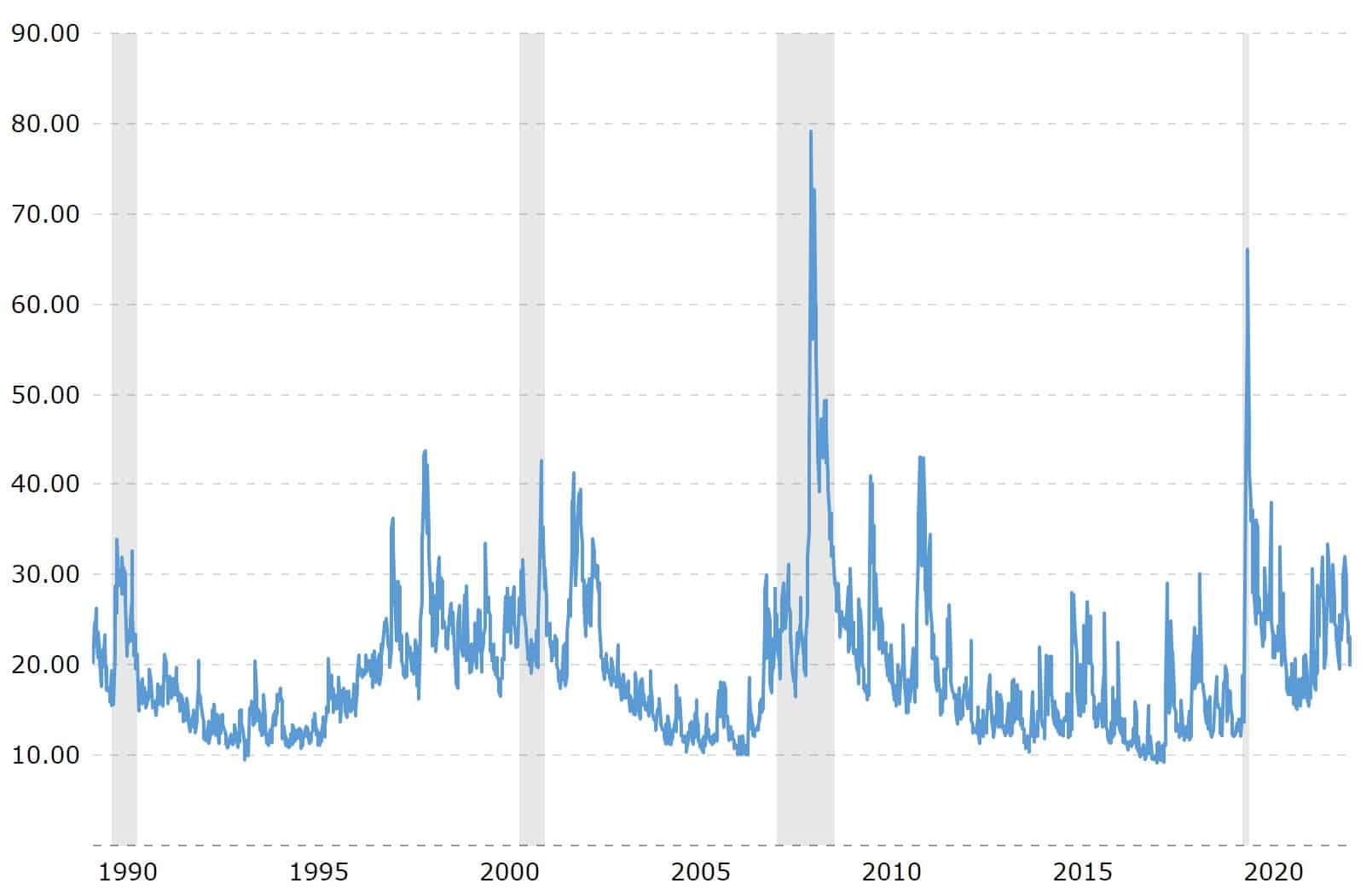

CBOE Volatility Index (VIX)

Enter, the CBOE Volatility Index (VIX). Recorded since the end of 1989, the VIX measures the market expectations for the magnitude of short-term price changes in the S&P500. It does this by deriving ‘implied volatility’ from 30-day forward options. Put simply, the VIX is a fair gauge of market sentiment, and the higher the index, the greater the level of fear, stress and (implied) volatility.

Aside from the obvious observations, the above graph tells us that on average, the sensitivity of investors to market conditions appears to be the same as ever.

“But why is the VIX so low during the 1990’s recession, dot-com crash, and especially the present day?” I can hear you ask. Well firstly, it is easy to lose perspective of the above diagram when you have the exceptional results of the GFC and early 2020 to contend with. But as a rule of thumb, VIX values greater than 30 are generally considered to be high and associated with large volatility, whereas VIX values below 20 generally correspond to periods of stability. On this basis, the VIX is certainly elevated. If you were to still insist that the VIX is low for the current market climate, I would give you three reasons. Firstly, there is an increase in hedged market positions since March 2020. Secondly, the rise in intraday reversal of the S&P500 moderates the VIX since investors are trading options on both positive and negative volatility. Thirdly, and most importantly, the VIX measures implied volatility only, and traders simply aren’t expecting significant movements in the S&P500 within the next 30 days. This is consistent with market commentary, particularly in Western countries, that markets are in holiday-phase, and may be under-pricing the incoming wave of company earnings downgrades.

A Quick Review of the Literature

What does the research say about the question we have posed?

Whilst more than 20 years old at this point, a landmark study published in 2000 by Campbell et al, ‘Have Individual Stocks Become More Volatile? An Empirical Exploration of Idiosyncratic Risk’ still adds value to the volatility discussion. This study found that while there’s no trend toward increased volatility at the market level, there is a significant trend of increasing “idiosyncratic” volatility at the individual firm level. They suggest several reasons for this, including the decline of conglomeration and rise of specialisation within companies, the increase of early-stage equity financing, and the increase of company leverage. I believe the identification of these trends were ahead of their time, as all three are clearly observable in the current market. Therefore, I am happy to extend their findings to a comment on modern market volatility.

Another important piece of research is the inelastic market hypothesis by Xavier Gabaix and Ralph S. J. Koijen. To oversimplify, this theory states that the emergence of the efficient-market hypothesis in the 1960’s has led to the meteoric rise of index funds. i.e. a significant increase in the amount of invested funds which respond little or slowly to movements in prices or new information. i.e. i.e. an increase in the inelasticity of markets. This gives an outsized influence to active traders such as hedge funds, who Gabaix and Koijen showed to have the largest impact on valuations despite holding less than 5% of the equity market. Whilst I am not prepared to extend this to a comment on retail investors, their findings are still worth mentioning. As part of this theory, they also observed the multiplier effect of capital flows to and from equity markets. Remarkably, they observed that for every $1 put into the market, aggregate prices increase by $5. It is not a large step then, to suggest that the increase of capital flows into the stock market in modern times, has led to a corresponding increase in market volatility – at least on a short-term basis.

Potential Explanations

If we assume for the moment that markets are indeed “more volatile than they used to be” without getting into the specifics of why this is, what might be some potential explanations?

- The increase in accessibility of share trading to retail consumers, largely through mobile apps. This has shifted market power away from larger, slower-moving, red-tape-bound, institutional investors that have historically dominated the market.

- The educational role of social media in regards to investing, and its subsequent normalization and widespread adoption. Said another way, financial literacy has become trendy among young people. So too has the “hustle, grind and invest” mentality. Even in recent years with the likes of Tik Tok and Twitter, the impact of these platforms is unmistakable.

- The boom in life expectancies of the past several decades, coinciding with the unstoppable wave of retiring baby boomers, leading to more middle and old-age people taking an interest in their investments. This is clearly reflected in the growing demand for financial advice in Australia.

- The race to zero brokerage across trading platforms, significantly reducing barriers to high frequency trading.

- The widespread publicity of short-term stock market fortunes and the resulting FOMO. This was especially the case for cryptocurrencies and U.S. tech stocks, both trading at eye-watering valuations. It should be unsurprising then, that these were the first to fall in the recent stock market correction. This point around FOMO should not be understated either, as everyone thinks they are above it until suddenly they aren’t. As someone who works in the financial advice space, you would be surprised at the number of retirees in recent years who have asked whether they should invest their retirement savings in cryptocurrency – the same generation of investors who should love nothing more than cash, bonds, and high dividend yields.

- The rise of uninformed investor demand and the gamification of trading. How about on January 26th 2021, when a tweet from Elon Musk sent the Etsy share price (NASDAQ:ETSY) up almost 10%, for simply saying that he purchased an item for his dog on the marketplace and enjoyed the experience? Not to mention the subreddit r/WallStreetBets sending Gamestop Corporation shares (NYSE:GME) soaring more than 1700% at the start of 2021, or the Western Australia-based nickel mining company GME Resources Limited (ASX:GME) that rose more than 50% with countless novice investors mistakenly thinking it was the same thing. Increasingly, investors have demonstrated a willingness to purchase securities purely on the notion that someone else will be willing to pay more. The explosion of NFT’s is another example of this.

- The information age, encompassing the growth of computers and Wi-Fi. Whilst this point is baked into many of the above, it is worth mentioning on its own.

TLDR

So… Is the share market more volatile than it used to be?

The short answer is yes. The current market environment is undoubtably more volatile than the long run average, as we are faced with high inflation, geopolitical instability, supply chain issues, and the end of a decade-long bull market. Few people are questioning this, however many are confusing volatility with simply losing money on their investments.

On an individual stock basis, the answer is also yes. For all of the reasons listed above, which can be loosely summarized as technology, trends, and changes in the investor demographic. This observation is consistent with the empirical studies referenced above, detailing the rise of company idiosyncrasies and growing market inelasticity.

However, if we are talking on a long-term, market-wide basis, compared to the course of history, the answer is no. The market is just about as volatile as it always has been, and the recent market downturn is no exception. Human nature is unchanged. We are simply out of practice for these kinds of market conditions, and we have short memories. Few people were talking about the positive market volatility experienced throughout 2021, and even fewer about the 2010’s being the least volatile of the previous 4 decades. It is only when the market starts to pull back that we ask these questions, which alone speaks volumes.